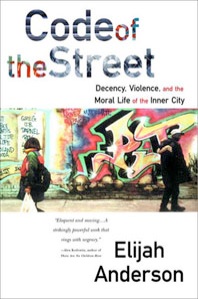

Code of the Street

Code of the Street

Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City

Elijah Anderson (Author, Yale University)

Overview | Inside the Book

Unsparing and important. . . . An informative, clearheaded and sobering book.—Jonathan Yardley, Washington Post (1999 Critic’s Choice)

Inner-city black America is often stereotyped as a place of random violence; in fact, violence in the inner city is regulated through an informal but well-known code of the street. How you dress, talk, and behave can have life-or-death consequences, with young people particularly at risk. The most powerful force counteracting this code and its reign of terror is the strong, loving, decent family, and we meet many heroic figures in the course of this narrative. Unfortunately, the culture of the street thrives and often defeats decency because it controls public spaces, so that individuals with higher, better aspirations are often entangled in the code and its self-destructive behaviors. Writing in the tradition of Jane Jacobs and William Julius Wilson, the author delineates the true workings of city streets. His most interesting characters are not the bullies and dealers, but the decent folks, young and old, who through entrepreneurship and creative self-help strategies are forging a viable alternative, an escape from the code of the street. Winner of the Komarovsky Book Award, this incisive book examines the code as a response to the lack of jobs that pay a living wage, to the stigma of race, to rampant drug use, to alienation and lack of hope. An individual’s safety and sense of worth are determined by the respect he commands in public—a deference frequently based on an implied threat of violence. Unfortunately, even those with higher aspirations can often become entangled in the code’s self-destructive behaviors.

BOOK DETAILS

Paperback

September 2000

SBN 978-0-393-32078-7

5.5 × 8.3 in / 352 pages

Territory Rights: Worldwide

ENDORSEMENTS & REVIEWS

“One of the most interesting examinations of poverty, violence and sociology to emerge in recent years.” — Boston Herald